Is Grocery Store Price Gouging Real?

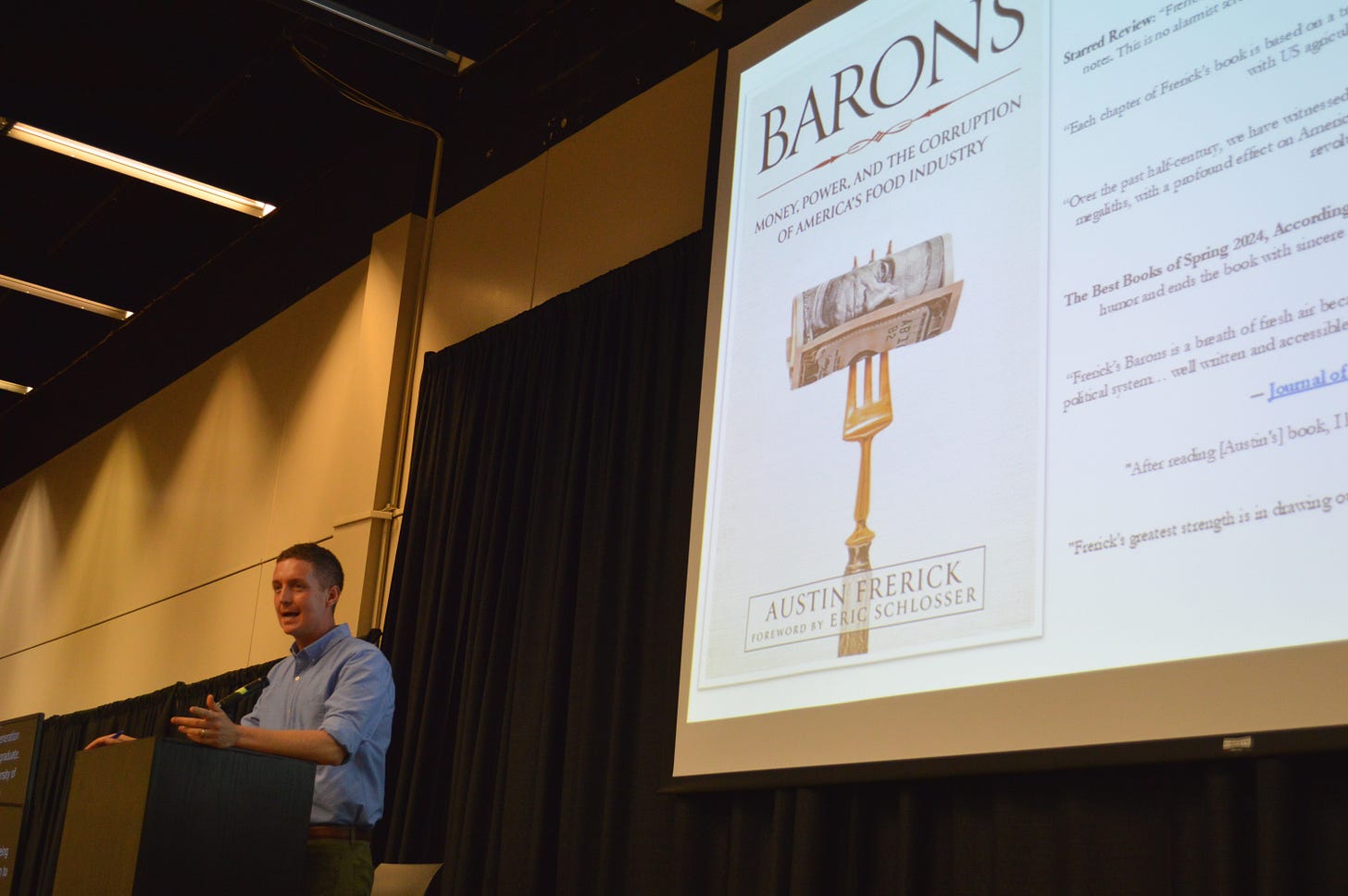

Austin Frerick on grocery store prices, the election, and how the government subsidizes corn so heavily we find it in our gas, our food, and our animal feed.

Austin Frerick and I grew up 30 minutes away from each other. The first time I interviewed him, we talked about Sushi Popo (R.I.P.) in the strip mall on the west side of Iowa City, Caitlin Clark, and the “hog barons” in his book. We grew up in bubbles, Cedar Rapids and Iowa City, slightly shielded from the ways our home state has failed many of its residents. Now, we’re connected in our shared interest of writing about the issues that have always surrounded us.

In August, I saw Frerick and economist Jason Furman tweeting in tandem about the hottest topic in food news: grocery store prices. Furman insisted that grocery store price gouging was not real. Frerick disagreed.

What better topic to dive into than the topic politicians, economists, and journalists (guilty as charged) can’t stop talking about? Here’y my Q&A with Barons author Austin Frerick.

Note: this interview has been edited for clarity.

Nina: Could you give an “Explain Like I’m Five” definition of price gouging?

Austin: Oh, man, that's such a good question, because I feel like there's an academic definition, and then there is what the average American thinks is price gouging. I feel like when most people hear it they think about how you're not paying a fair price for something. Like they're purposefully milking you. I'm actually pulling up Merriam-Webster right now.

What I love about your question is it really gets to the point of how what is “price gouging” is so subjective, in the same way that “consumer welfare standard” is in the antitrust world. People in Ivory Towers think there's a formula or science to this. At the end of the day, what is price gouging? It’s just an unfair price. They try to make it much more than that, but it's really not. Economists like to think there's a highbrow science to it, and that there are astrologers that can interpret the signals, but…no.

There seems to be some fear mongering going on about what might happen if Kamala Harris, if elected, bans price gouging. Harvard economist Jason Furman wrote that “there are no upsides, only downsides,” to this.

Let’s just start with Jason Furman. What really bothers me among the professional elite of America is this kind of “save face” culture, where you talk around everything. There's this notion, especially with people with fancy titles, that they are these wise owls giving us their knowledge. Jason Furman comes from a family that made its fortune doing real estate deals with Walmart. He's a trust fund kid. He doesn't disclose this. He doesn't talk about this. I think this should be part of the conversation with anything he says about this, given how he's able to essentially pursue a certain career option because of his family's transactions with America's largest retailer.

You're seeing a low-key undercurrent battle between Democrats. There’s a certain crowd, this really corporatist crowd, like Jason Furman and Matthew Yglesias, who are almost just hacks for industry at this point. Both of them, I believe, went to prep schools (Editor’s note: true. They both went to The Dalton School in Manhattan). They just don't get the average American life and what's happened to most people and the pain people feel. One lives in Cambridge, one lives in D.C., and life might be good in those worlds, but a lot of other people would disagree. I see them not understanding and just wanting to reinforce the current structures and not make actual, meaningful change. So anyone that's trying to do change, they're essentially trying to smother or undercut.

That’s my hot take.

I'm sure it's a hot take in those circles. How are executive salaries and people at the top of corporations tied to price gouging?

There has been some inflation these last few years. You can raise prices for inflation. You can raise them $1 or you can raise them a quarter and hide a little profit in there, a little gouging. And it's really easy to do that when markets are really concentrated. I think the under appreciated thing here too is, back in the day, you would act like a cartel. All these executives met in hotel rooms. We don't live in that time anymore. You have these data brokers that essentially allow you to do that now. Most famously, you have Agri Stats, where these third parties gather data on the industry. Each individual actor buys into that dataset and knows what everyone else is doing without coordinating. So it allows you to coordinate without coordinating, so you could still get those profits without getting caught and wasting your time in a hotel room.

Barons talks a lot about this. So just bear with me, because I'm going to read something from your book. You write, “You would never guess these markets are so consolidated from a casual trip to the grocery store. You can look at a shelf of peanut butter and think you’re seeing a competitive market, with a range of options like Jif, Smucker’s, Adams, Laura Scudder’s, and Santa Cruz Organic. But all these brands are owned by the J.M. Smucker Company, which now sells nearly one in every two jars of peanut butter directly.” How does this kind of consolidation, which, as you said, is happening maybe not in hotel rooms, but it's still happening, impact our sense of price gouging and prices?

That's one of my favorite examples of the illusion of choice. Just add in the fact that most of these companies do the store brand, too, and you only find out about it through food recalls.

This illusion of choice hides consolidation in the food space. It's not just one name on everything that you see everywhere. You think these are competitive markets because you see these different brands without realizing what's going on behind the scenes. The concentration crisis in the American food system is under appreciated because of that. The rule of thumb with institutional economists is that four companies own 40 to 60% of a market. I don't need a Ph.D. in economics to know that people aren't paying a competitive price there. Peanut farmers aren't getting a fair price either.

The purpose of my newsletter is to bring everything back to the Corn Belt. How is all of this tied to commodities like corn and soybeans and the consolidation happening there?

It's everything. If there was a table, corn would be the queen bee commodity. Corn is what drives everything, and it's because it gets the most subsidies. We subsidize everything to some degree. The question is to what extent. And corn? We give so many subsidies to corn to make cheap pops and chips. We give almost nothing to carrots. So that's why you see corn in everything now.

It’s why you generate artificial uses for it, things like ethanol, because every year the system is designed to produce corn. It’s just more corn, more corn, more corn. Instead of saying, well, let's grow grapes, let's grow rye. How do you find new uses for the surplus? Marion Nestle has done a good job of pointing this out. It's why processed foods have gotten relatively cheaper than healthy foods.

It’s really interesting, as you said, how that ties into the illusion of choice. The foods that we are being pushed toward, or that we have the option to eat at a cheaper price, are being controlled.

It's a farm bill built for Wall Street wands because corn has a long shelf life. Carrots don't. Walmart doesn't want to have a different local produce provider for each store. It wants one company that can make the same corn product for all 4000 stores. It can be in a warehouse for months.

Food in America just doesn't taste good anymore. I think it's because of this obsession over corn. Corn’s almost become a cancer cell in the Midwest. The Corn Belt keeps going. It keeps sprawling into other farmland. It crowds out everything else. Everything else is moving offshore. As these supply chains get long, transparency and taste collapse.

I went to the new HyVee in Grimes a few weeks ago. I wanted to see it because it's a new prototype store. Here I am in a grocery store in Iowa in July, and none of the produce is from Iowa. Iowa grows the best tomatoes, especially in July. I can't get one in the store. I look at this produce. It's overpriced. It doesn't look good.

Is there anything else you'd like to add on price gouging, or that you think people should know?

This will continue to happen until we deal with these concentrated market structures. It's a fact of life until we handle the problem at hand. The question here really is political courage. When these businesses get caught, they view it as a cost of doing business. We should expect this to continue until we actually have the political courage to do something meaningful here. The really scary thing here is this presidential election will come down to a few voters in a few states over grocery store prices. The failure of Secretary Vilsack to do anything meaningful here on such a bipartisan issue really undermines the Vice President's campaign.

Vilsack gave an interview to Iowa Starting Line where he just did not believe in antitrust. He is pro-consolidation. He thinks companies need to be big for innovation. Vilsack is just Earl Butz with a better smile.

My latest stories:

13 Groups Sued EPA Demanding Stricter CAFO Regulation — the Court Struck Them Down

A Carbon Capture Monitoring Well Leaked in Illinois. Most Residents Found Out When the World Did